In August 1914, 1st Battalion of the regiment was stationed at Richmond Barracks in Dublin, where it had been since the autumn of 1911. They had not seen active service since the early part of the century in South Africa and had otherwiseseen action in Aden or been on garrison duty in Ceylon and Malta. Despite their lack of recent action, it was a well-disciplined and well-trained unit and had no difficulty in recruiting from its own area in the south-east. Recruits were as likely to come from Greenwich and Lewisham as they were from Sevenoaks, Tonbridge, and the more picturesque heart of the Kent Weald, in places such as Sissinghurst and Cranbourn.

Those men on the Army Reserve were recalled and the Battalion received reinforcements of reservists before departing for Le Havre. On 6 August 320 reservists arrived from Maidstone, the Regimental headquarters, followed by another 270 the following day. Two hundred underage men had to be replaced along with a handful of “unfits”, some of whom were left to guard duty in Dublin; eight underage men, along with two junior officers were temporarily assigned as railway transport staff at Kingsbridge station.

Thus, the battalion became a mix of serving soldiers and men who had not been subject to the rigours of army life for some time. The newly arrived reservists, out of the Army for up to nine years, were put through their paces in an attempt, as Major Molony noted in his history of the Battalion ”…to remove the rust occasioned by their more or less prolonged absence from the service.” Lieutenant Horace Vicat was charged with getting these men back into some sort of shape, writing home to his mother in Sevenoaks “It looks rather fine with a thousand men in the battalion, instead of about five hundred or less.” According to the War Diary “The men were exercised under company arrangements in platoon drill and musketry.”

Mobilisation was completed by August 11, but it was not until the early hours of 14th after some delay, that the battalion, at a strength of 26 officers and 1015 men, accompanied by 62 horses, left Dublin’s Alexandra Basin on the SS ‘Gloucestershire’. As it sailed, the battalion was a mix of regulars and the freshly returned, coping with new uniforms and unfamiliar equipment, and varying degrees of competence or recent regular practice in musketry. Perhaps they reflected Sir Arthur Wellesley’s comment on the West Kents of over a century earlier, “Not a good-looking regiment, but devilish steady.”

Although on arrival at Le Havre in the afternoon of 15th, they were greeted by torrential rain, the men would soon be marching during one of the hottest summers on record and would shortly be facing the might and numerical superiority of the German army.

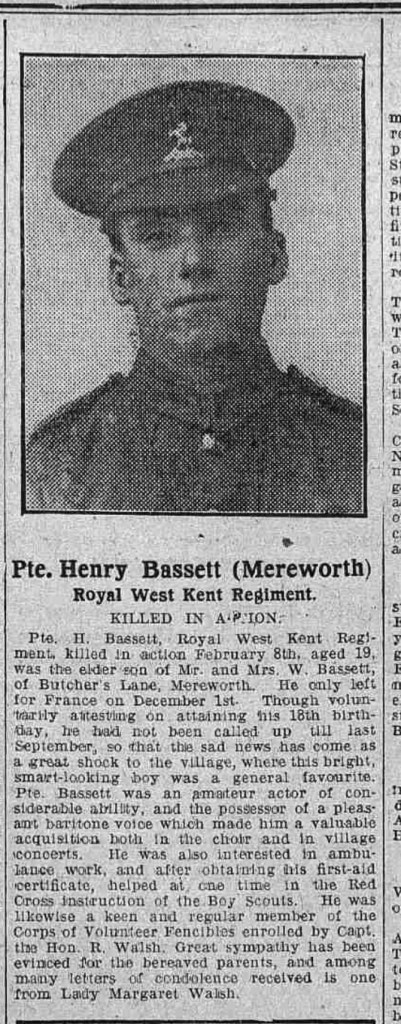

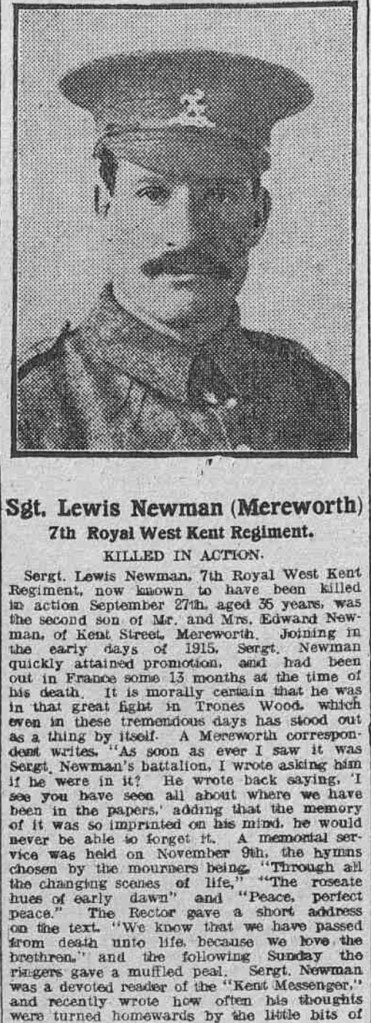

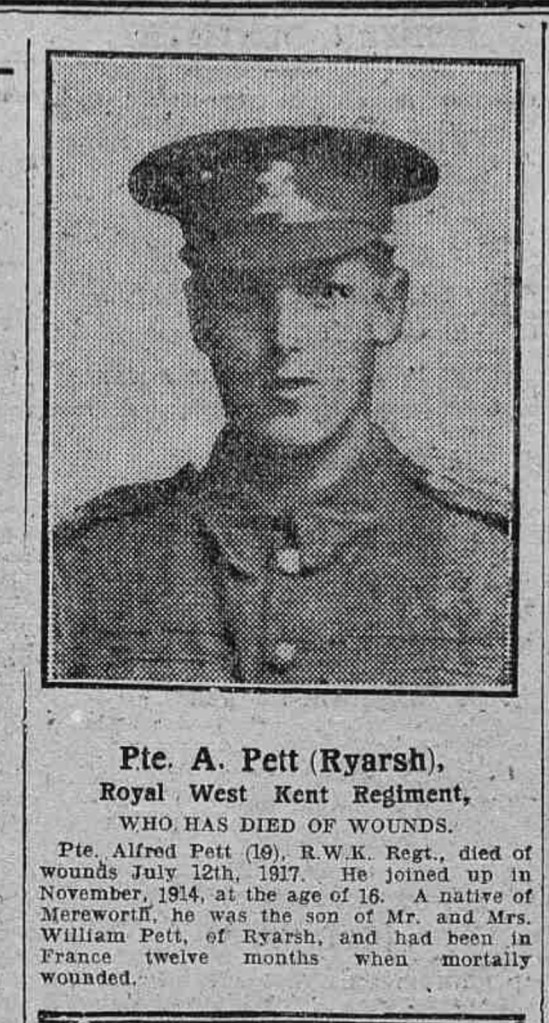

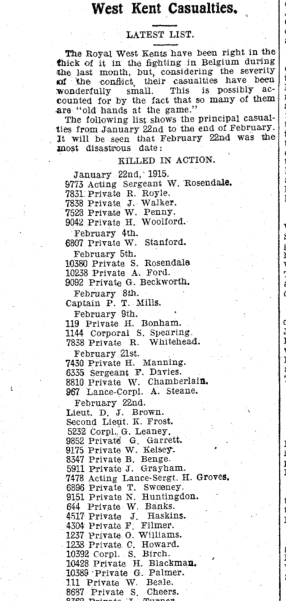

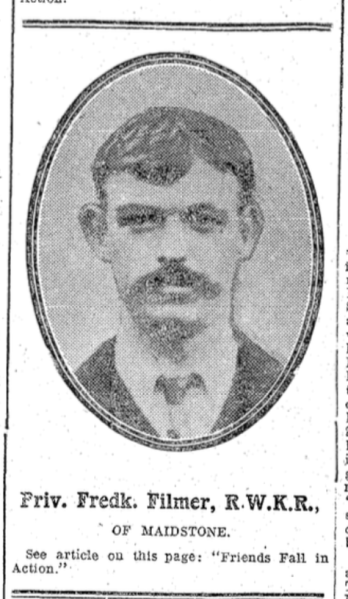

How the men fared, their background, what they thought of their experiences, is the subject of my ongoing research, and was documented in numerous letters home or interviews with local journalists. The exploits of the ‘Glorious West Kents’ were used as an inspiring example in the various recruiting meetings taking place across at home across the county.

By the time Le Havre was reached, at 2.30pm on the 15th, the rain was torrential. The next day the Battalion marched five and a half miles to a rest camp. They were swamped by the locals, with many seeking a shoulder or cap badge as a souvenir as well as proffering gifts. Off the West Kents went on the 17th August. The destination was Landrecies. The journey, with the entire battalion carried on one train, some forty men to a truck, took them through the north French countryside. All along the route the men were showered with gifts from a grateful local population. Lance Corporal Clarke of Yalding in Kent was one of those stationed in Dublin with the battalion before the war. Later wounded and sent to NetleyHospital, before returning to his parents at Maidstone to recuperate, he recalled that before entraining for the front the people of Havre gave the battalion a wonderful reception, and simply pressed group gifts of food, fruit, cigarettes and wine upon them. The French people could not do enough for “the brave English”.

Landrecies was reached around midnight and the Battalion detrained and marched to billets a couple of miles away at La Basse Maroilles. A few days later on 21st and the battalion marched in hot weather to billets at Houdain. The heat of the summer had taken its toll on the Battalion, particularly the reservists, who were now more familiar with civilian life. Additionally, the equipment issued proved unsuitable for the time of the year. The 1908 pattern web equipment had been issued to the battalion in October 1909, so that any reservists who had left before that date had never carried it before.

Harry Beaumont, a native of Kent, from Blean and a recently recalled reservist remembered; “We were saddled with pack and equipment weighing nearly eighty pounds and our khaki uniforms, flannel shirts and thick woollen pants, fit for an Arctic climate, added to our discomfort in the sweltering heat. By midday the temperature had reached ninety degrees in the shade! We were soon soaked with perspiration, and all looked almost as if they had been dragged through water!”

By August 21 the battalion arrived in the Mons area and went into billets overnight. The following morning their march continued till they reached a position north of St Ghislainwhere they spent the afternoon entrenching close to the Mons Conde Canal. The previous afternoon the battalion had been addressed, alongside others, by Major General Fergusson, commanding 5th Division. The battalion’s War Diary noting soberly that his remarks could be distilled to the following observations: 1. Necessity for discipline; 2. We are now “up against it”; 3. Characteristics of the enemy, and 4.to fight to the last.

Arrival at Mons

The Battalion strength formed a quarter of the 13th Infantry Brigade in the 5th Division of the 2nd Corps of the British Expeditionary Force. Other regiments of the Brigade being the 2nd Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, the 2nd Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s and the 2nd Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. The two Corps of the BEF were brought up to conform with the line of French resistance to the German advance on Paris.

Owing to the French retreating, the original plan to form a line running from Charleroi through Binche to Mons was abandoned, Charleroi having fallen to the Germans. The British hand was therefore forced.

The First Corps was positioned along the Beaumont – Mons Road, whilst the Second Corps was to man the canal between Mons and Conde. The latter position seen as a temporary, delaying one. Smith Dorrien had readied a more defensible position to the rear through Framieres, Pasturage Wasmes and Bossu.

The canal position was reasonably strong excepting for a salient jutting north on the right of the line at Nimy. (The line readied by Smith Dorrien was never taken up, as the Britishwere ordered to retire in accordance with the French).

The Royal West Kents reached St Ghislain on 22 August. C and D Companies were posted on the bridges north and north east of the town. A and B Companies were in the village in reserve. The day was spent in taking the necessary defensive measures; loopholing, barricading and preparing trenches.

Early on 23 August the job of supporting reconnaissance by19th Hussars and Cyclists of 5th Division on the north side of the canal, and covering their retirement if necessary, was detailed to Captain George Lister’s A Company. On reaching the crossroads just south Tertre, Captain Lister deployed his Company: No 1 Platoon under 2nd Lieutenant Gore at A (map below), No 2 Platoon under Lt Wilberforce Bell at B No 4 Platoon under Lt Anderson at C No 3 Platoon under 2nd Lieutenant Chitty was kept in reserve just behind No 2 Platoon at B.

Captain Lister set his men the task of preparing the ground and bettering the existing cover plus making sure that the fields of fire were the best available. No sooner had this been done and a report sent to Battalion Headquarters in St Ghislain when in Lister’s words “These preparations were scarcely complete when I saw four cyclists with an officer coming at full speed down the road from Tertre. On arriving at our position they flung themselves down by me, and the officer in charge stated the remainder of his detachment had been blown to pieces by the enemy’s artillery fire.”

Lister sent another update to Battalion Headquarters and made the decision to hold the position for as long as possible. He reinforced Number 1 Platoon’s position at A with half of Lieutenant Chitty’s Platoon.

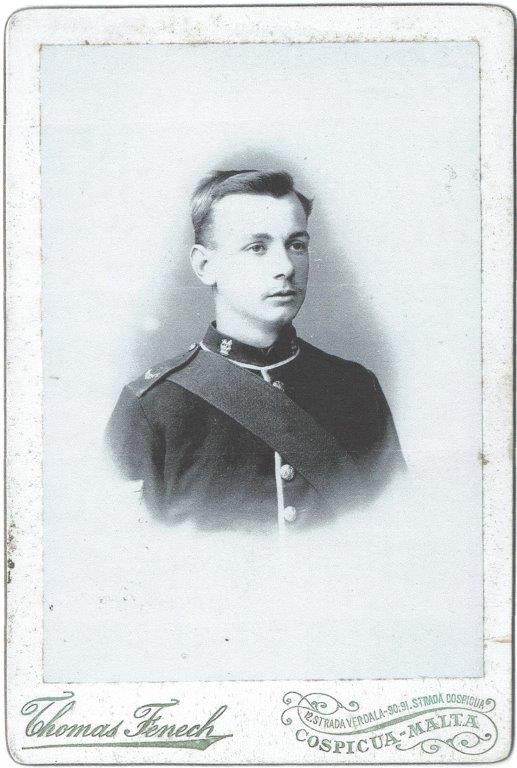

Arthur Chitty was a fresh faced eighteen year old Sandhurst recruit. His boyishness and inexperience moved an old sweat, Private “Onion” Hill to comment, “Blimey, you mean to say a Gawd-forbid like that’s going to lead us into action? Reckon ‘e should have brought his bleedin’ nurse along wiv ‘im”.

The Germans emerged from Tertre and were greeted with a fierce fusillade from the West Kents. The cavalry whose retreat the troops were covering were still nowhere to be seen. The sheer size of the German invading force took its toll on A Company and the order to retire was given by Captain Lister, his detachment having lost over a hundred men.

Lister later recalled “I saw the enemy’s infantry emerging from Tertre in large numbers. I counted on the east side of the road some 400-500 men. Fire was at once opened upon them and it could be seen that the enemy was suffering considerable loss. After a short time, he returned the fire heavily. Since the action I have ascertained that in my immediate front the Germans had three Battalions of the Brandenburg Grenadiers, one Battery of Artillery and one Machine Gun Company. The Officers, N.C.O.’s and men of the Company behaved well under difficult circumstances.”

The connecting post at E (see map) reported that Number 1 platoon had got away, however around twenty men of Number 4 platoon were trapped along the western side of the main road. Lister moved across to issue instructions to them, but he received a wound to the right shoulder. Two of his men stopped to collect him, but he ordered them back to the main body of the Battalion in St Ghislain. He was later tended to by one of the advancing Brandenburg Grenadiers. Chitty received a wound to the chest and one to the arm. A keen cricketer, in his own words he, ‘Was out first ball”.

The Hussars finally came across to the south side of the canal followed by the surviving remnants of A Company of the West Kents. About ninety of A Company came in from the original two hundred. Many of the German infantry also lay dead and wounded across to the north of the canal.

The Germans now turned their attention towards the defensesin St Ghislain itself and the houses in the town began to be shelled. The Germans crept forwards and made a few tentative attacks, but when fired on quickly took cover from a ridge running parallel to the canal.

The West Kents were well prepared; D Company held the railway bridge over the canal, with trenches dug into the railway embankment. The trench was covered with cinders and the tracks camouflaged. A dummy trench was also dug which drew a lot of the fire. The German artillery, around thirty guns, was roughly 1800 yards away. C Company were manning the road bridges to the north still. B Company helped to man Battalion Headquarters and reinforce C Company. By nightfall on the 23rd the German attacks had got to within 200 yards of the West Kents, but the attacks were limited and unsuccessful in the face of rifle fire by the West Kents.

Harry Beaumont with B Company was in a position in a glass factory in the town. In his war memoir, Old Contemptible, he recalled “The country in front of our position and dotted with numerous circular fenced-in copses, a common feature of that part of Belgium. The Germans, moving forward between them, made easy targets and we opened fire. Their losses that afternoon must have been tremendous.”

“By 10.00 pm they had advanced so close that we could hear them talking! Hearing no sound from us they had naturally came to the conclusion that we had withdrawn and small fires began to spring up all over the place, presumably for cooking their evening meals. This was asking for trouble on their part and just to show them that we were still here, and taking those fires as our targets, we opened out with fifteen minutes rapid fire, known in the Army as the ‘mad minute,’ that ‘mad minute’ which led the German High Command to think, during the early days of the war, that the British Infantry were heavily armed with machine guns!”

The canal was never meant to be held for long and the order to retire was given. (D Company’s position was also compromised as the enemy had started to cross the road bridge adjacent to the railway bridge). There were a total of six bridges and locks on the Battalion’s front that would need to be blown during the retirement. A detail was sent to ‘pick’ the road to give the impression of digging and entrenching. By 01.00am on 24 August all of the Battalion was back over to the south of the canal and at 01.30am the bridges were blown. By 04.00am on the 24th the Royal West Kents were in the main square at Wasmes and the retreat from Mons was underway.

The 12th Brandenburg Grenadiers had faced A Company. German officer, Captain Walter Bloem’s memoirs give credit to the men of the Royal West Kents

“The enemy seems to have waited for the moment of a general assault. He had artfully enticed us to close range in order todeal with us more surely and thoroughly. A hellish fire broke loose and in thick swathes the deadly leaden fire was pumped on our heads, breasts, and knees. Whenever I looked, to the right and left, nothing but dead, and blood-streaming, sobbing, writhing wounded.”

Whatever the truth of the ‘mad minute’ clouded by myth and memories, there is no doubt that the West Kents fought well, and the efficacy of their gunfire is mentioned in a number of German sources. Bloem’s company saw heavy losses:

“Heavy defeat, why not admit it? Our first battle is a heavy, unheard of heavy defeat, and against the English, the English we laughed at.”

The Royal West Kents were among the first British Infantry to confront the Germans in the war; their steadiness, coolness under fire and ability to inflict high casualties against the Brandenburg Grenadiers confounding German assumptions of the “contemptible little army”.

Many thanks to Neil Bright, Nigel Bristow, and Nick Britten for their advice on this piece.